Understanding competitive dynamics is crucial for sustainable success.

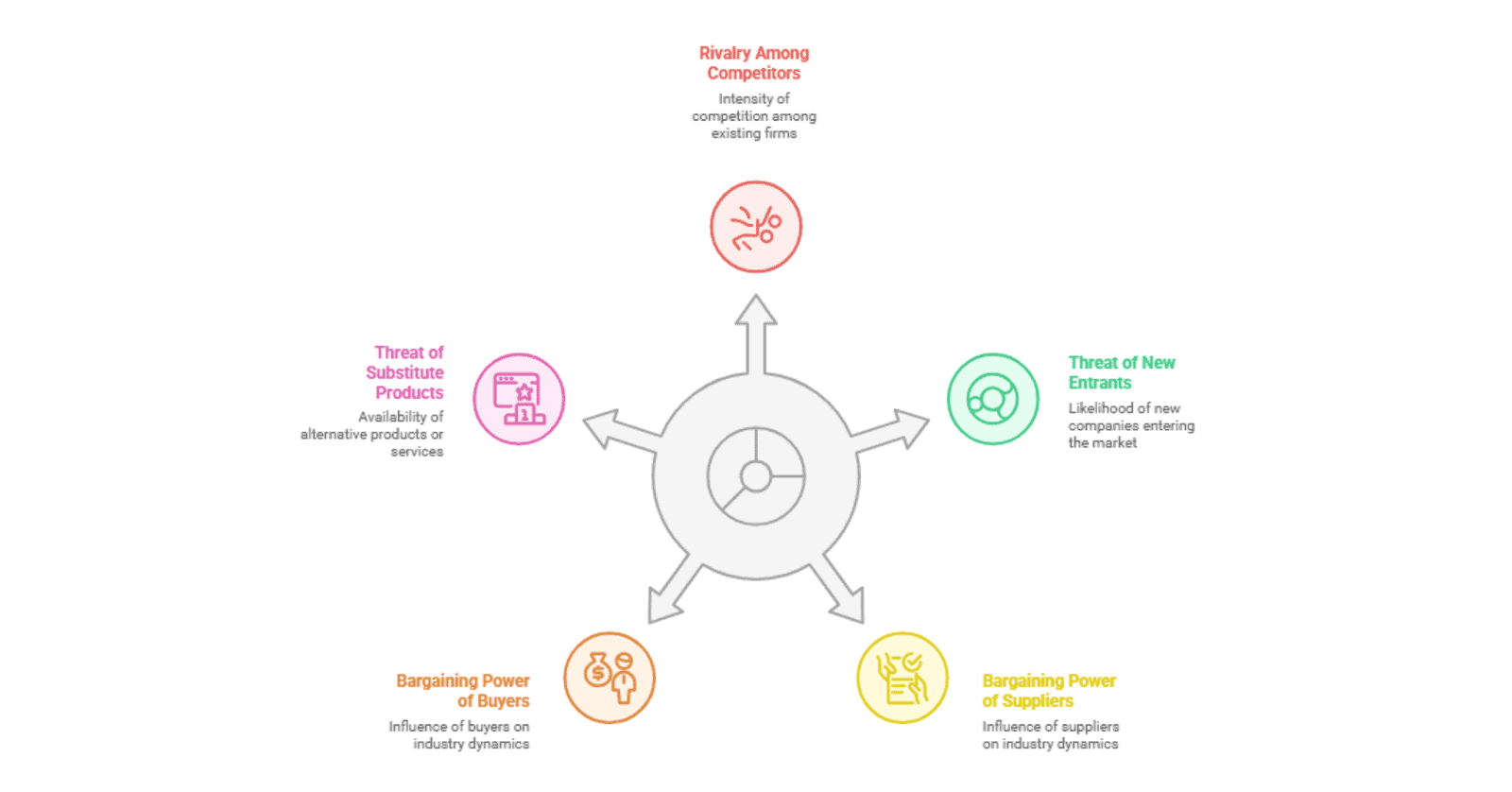

Porter’s Five Forces framework stands as one of the most influential and enduring strategic analysis tools, providing businesses with a systematic approach to evaluate industry attractiveness and competitive positioning. This powerful framework helps organizations identify the key forces that shape competition within their industry and develop strategies to achieve competitive advantage.

What is Porter’s Five Forces Analysis?

Michael Porter developed the five forces model in 1979 as a tool for analyzing industry competitiveness. A Harvard Business School professor he is well known for his work on competitive strategy.

The analytical model identifies and analyzes five competitive forces that shape every industry and help determine an industry’s weaknesses and strengths. The framework provides a structured method for analyzing the competitive environment and understanding the underlying drivers of profitability in any industry.

The five forces work together to determine the intensity of competition and profitability of an industry. When the forces are intense, companies can earn attractive returns. However, when the forces are strong, few companies can command attractive prices or earn attractive profits. Understanding these dynamics enables businesses to position themselves advantageously and develop strategies that improve their competitive position.

Porter’s model revolutionized strategic thinking by shifting focus from internal company factors to external industry dynamics. It demonstrates that a company’s profitability is not just determined by its own efficiency and innovation, but significantly influenced by the structural characteristics of the industry in which it operates.

The Five Competitive Forces

1. Threat of New Entrants

The threat of new entrants refers to the possibility that new competitors will enter the industry and reduce the profitability of existing players. This force examines how easy or difficult it is for new companies to enter the market and compete effectively with established firms.

Key factors influencing barriers to entry include:

Economies of Scale: Industries where large-scale production leads to cost advantages create barriers for new entrants who cannot immediately achieve similar scale. Established companies benefit from spreading fixed costs over larger volumes, making it difficult for newcomers to compete on price.

Capital Requirements: High initial investment requirements can deter new entrants. Industries requiring substantial upfront investments in equipment, facilities, research and development, or marketing create natural barriers that protect existing players.

Product Differentiation: When existing companies have strong brand loyalty and customer relationships, new entrants must invest heavily in marketing and product development to overcome these advantages. Industries with high customer switching costs also create barriers to entry.

Access to Distribution Channels: Existing companies may have exclusive relationships with distributors or control key distribution channels, making it difficult for new entrants to reach customers effectively.

Government Policy and Regulation: Licensing requirements, patents, regulations, and government policies can create significant barriers to entry. Industries like pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, and financial services often have substantial regulatory barriers.

Expected Retaliation: If new entrants expect existing companies to respond aggressively to their entry through price wars, increased advertising, or other competitive actions, they may be deterred from entering the market.

When barriers to entry are high, the threat of new entrants is low, and existing companies can maintain higher profitability. Conversely, low barriers to entry increase competitive pressure and typically reduce industry profitability.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers

The bargaining power of suppliers examines how much control and influence suppliers have over the industry. Powerful suppliers can squeeze profitability by raising prices, reducing quality, or limiting the availability of their products or services.

Factors that increase supplier power include:

Supplier Concentration: When there are few suppliers relative to many buyers, suppliers have more power to dictate terms. A concentrated supplier base can coordinate actions and maintain higher prices.

Uniqueness of Supplier Products: Suppliers offering unique, differentiated products or services that are difficult to substitute have more bargaining power. This is particularly true for suppliers of critical inputs or specialized components.

Switching Costs: High costs associated with switching suppliers give existing suppliers more power. These costs might include retraining, retooling, new contracts, or technical integration challenges.

Forward Integration Threat: When suppliers have the ability to integrate forward into the buyer’s industry, they have additional leverage. The credible threat of bypassing current customers and selling directly to end users increases supplier power.

Importance of Volume: If the supplier’s product represents a small portion of the buyer’s costs, buyers may be less price-sensitive, giving suppliers more pricing power.

Lack of Substitute Inputs: When there are few alternatives to the supplier’s product, suppliers maintain stronger bargaining positions.

Understanding supplier power helps companies develop strategies for supplier relationship management, vertical integration decisions, and supply chain diversification.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers

The bargaining power of buyers focuses on the ability of customers to put downward pressure on prices and demand higher quality or more services. Powerful buyers can force down prices, demand higher quality, play competitors against each other, and generally squeeze industry profitability.

Factors that increase buyer power include:

Buyer Concentration: When buyers are concentrated and purchase large volumes, they have more negotiating power. Large customers can demand volume discounts and favorable terms.

Price Sensitivity: Buyers who are highly price-sensitive will aggressively seek lower prices and better deals. This is often the case when the product represents a significant portion of the buyer’s costs.

Product Standardization: When products are standardized with little differentiation, buyers can easily switch between suppliers, increasing their bargaining power.

Low Switching Costs: When it’s easy and inexpensive for buyers to switch suppliers, they have more leverage in negotiations.

Backward Integration Threat: Buyers who have the ability to integrate backward and produce the product themselves have additional leverage in negotiations.

Full Information: Well-informed buyers who understand market prices, costs, and alternatives have more power to negotiate favorable terms.

Product Importance: If the product is not critical to the buyer’s operations or represents a small portion of their costs, buyers may have more flexibility to negotiate or switch suppliers.

Companies can reduce buyer power through differentiation, switching costs, exclusive relationships, and by focusing on less powerful customer segments.

4. Threat of Substitute Products or Services

The threat of substitutes refers to the likelihood that customers will switch to alternative products or services that serve the same function. Substitutes limit the potential returns of an industry by placing a ceiling on prices and profits.

Key considerations for substitute analysis include:

Relative Price Performance: Substitutes that offer better value propositions through lower prices or superior performance pose significant threats. The price-performance ratio comparison is critical in assessing substitute threat levels.

Switching Costs: Low switching costs make it easier for customers to move to substitutes, while high switching costs provide protection against substitute threats.

Customer Propensity to Substitute: Some customer segments are more willing to try alternatives than others. Understanding customer behavior and preferences helps assess substitute threats.

Proximity of Substitutes: Close substitutes that serve the same function pose more immediate threats than distant substitutes that require significant changes in customer behavior.

Substitute Improvement Rate: Industries where substitutes are rapidly improving pose increasing threats over time. Technology-driven substitution often follows this pattern.

Substitute products don’t need to be identical to pose a threat. They simply need to serve the same customer need or function. For example, email substituted for postal mail, streaming services substituted for physical media, and mobile payments are substituting for cash and cards.

Companies can defend against substitutes through continuous innovation, strong branding, customer education, and by improving their value propositions faster than substitutes can catch up.

5. Rivalry Among Existing Competitors

Competitive rivalry refers to the intensity of competition among existing firms in the industry. This force is at the center of Porter’s model and is influenced by all other forces. High competitive rivalry typically leads to price wars, increased marketing costs, and reduced profitability for all players.

Factors that intensify competitive rivalry include:

Number and Size of Competitors: Industries with many competitors of similar size typically experience more intense rivalry than those dominated by a few large players or one clear leader.

Industry Growth Rate: Slow industry growth intensifies competition as companies fight for market share in a stagnant pie. Fast-growing industries often accommodate multiple successful players.

Fixed Costs and Storage Costs: High fixed costs create pressure to maintain high capacity utilization, leading to price competition. High storage costs can lead to price cutting to move inventory.

Product Differentiation: Low differentiation leads to commodity-like competition primarily based on price. High differentiation allows companies to compete on factors other than price.

Switching Costs: Low switching costs intensify rivalry as customers can easily change suppliers, forcing companies to compete aggressively for customer retention.

Exit Barriers: High exit barriers keep unprofitable companies in the industry, intensifying competition. These barriers might include specialized assets, high closure costs, or emotional attachments.

Strategic Stakes: When success in an industry is crucial for a company’s overall strategy, competitive intensity increases as companies invest heavily to win.

Understanding competitive rivalry helps companies choose competitive strategies, anticipate competitor actions, and identify opportunities for differentiation or collaboration.

How to Conduct Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Step 1: Define the Industry and Market

Begin by clearly defining the industry boundaries and market scope you want to analyze. This definition significantly impacts the analysis results. Consider geographic boundaries, product categories, customer segments, and value chain stages. Be specific about whether you’re analyzing a broad industry or a particular market segment.

Step 2: Gather Relevant Data and Information

Collect comprehensive information about the industry structure, key players, market dynamics, and trends. Use industry reports, company annual reports, trade publications, government statistics, and expert interviews. Ensure your data is current and relevant to your defined market scope.

Step 3: Analyze Each Force Systematically

Examine each of the five forces individually, using the factors outlined above to assess the intensity of each force. Rate each force as high, medium, or low intensity based on your analysis. Document your reasoning and supporting evidence for each assessment.

Step 4: Synthesize the Overall Industry Attractiveness

Combine your analysis of all five forces to assess overall industry attractiveness. Industries with weak forces (low threat of entry, weak supplier/buyer power, few substitutes, low rivalry) are typically more attractive and profitable than industries with strong forces.

Step 5: Identify Strategic Implications

Based on your five forces analysis, identify strategic implications for your organization. This might include market entry decisions, competitive positioning strategies, vertical integration opportunities, or exit considerations.

Step 6: Develop Strategic Responses

Create specific strategies to address the most significant forces affecting your industry. This could involve building barriers to entry, reducing supplier power, differentiating from competitors, or defending against substitutes.

Step 7: Monitor and Update

Industry forces change over time due to technological advances, regulatory changes, and market evolution. Regularly update your analysis to reflect these changes and adjust strategies accordingly.

Benefits of Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Porter’s Five Forces analysis provides numerous strategic benefits that make it an essential tool for business planning and competitive strategy development, including:

Industry Attractiveness Assessment: The framework provides a systematic method for evaluating whether an industry offers attractive profit potential. This is crucial for investment decisions, market entry strategies, and resource allocation priorities.

Competitive Strategy Development: By understanding the forces shaping competition, companies can develop strategies that improve their competitive position. This might involve building competitive advantages that are difficult to replicate or finding market positions that are naturally more defensible.

Investment Decision Support: Investors and companies use Five Forces analysis to evaluate potential investments, acquisitions, or new market opportunities. Understanding industry dynamics helps predict future profitability and growth potential.

Strategic Position Identification: The analysis helps identify the most attractive positions within an industry and understand what capabilities are needed to succeed in those positions.

Risk Management: By identifying potential threats from new entrants, substitutes, and powerful suppliers or buyers, companies can develop risk control and mitigation strategies and contingency plans.

Merger and Acquisition Analysis: The framework helps evaluate potential M&A opportunities by assessing how combinations might change industry dynamics and competitive positions.

Applications Across Different Business Contexts

Porter’s Five Forces can be applied effectively across various business contexts and decision-making scenarios, including:

Strategic Planning: Use the framework as part of comprehensive strategic planning processes to understand external competitive dynamics and inform long-term strategy development.

Market Entry Analysis: Before entering new markets, analyze the five forces to understand competitive intensity and identify success factors. This helps determine entry strategies and resource requirements.

Competitive Intelligence: Regularly analyze industry forces to monitor changes in competitive dynamics and anticipate strategic moves by competitors.

Product Development: Understanding substitute threats and buyer power helps inform product development priorities and positioning strategies.

Supply Chain Strategy: Analysis of supplier power helps develop supply chain strategies, including supplier diversification, vertical integration, and partnership approaches.

Pricing Strategy: Understanding buyer power and competitive rivalry provides insights for pricing strategy development and helps predict competitor pricing responses.

Limitations and Considerations

While Porter’s Five Forces is a powerful analytical tool, it has limitations that users should understand and address, such as:

Static Nature: The original framework provides a snapshot of industry conditions but doesn’t explicitly address how forces change over time. Industries are dynamic, and forces can shift rapidly due to technological change, regulatory shifts, or market evolution.

Industry Definition Challenges: The analysis results are highly sensitive to how industry boundaries are defined. Too narrow a definition might miss important competitive threats, while too broad a definition might obscure important competitive dynamics.

Interconnected Forces: The five forces don’t operate independently; they’re interconnected and influence each other. Changes in one force can trigger changes in others, creating complex dynamics that are difficult to predict.

Internal Factors: The framework focuses primarily on external industry factors and doesn’t explicitly consider internal company capabilities, resources, and strategic choices that significantly impact competitive success.

Technological Disruption: In rapidly changing technological environments, the framework may not adequately capture the potential for radical industry transformation or the emergence of entirely new competitive paradigms.

Network Effects and Ecosystems: In industries characterized by network effects or ecosystem competition, traditional five forces analysis may not fully capture competitive dynamics.

Best Practices for Effective Analysis

To maximize the value of Porter’s Five Forces analysis, consider these best practices that enhance the quality and usefulness of your analysis.

Use Multiple Perspectives: Involve team members from different functions and levels to provide diverse perspectives on industry dynamics. Sales teams understand customer power, procurement teams understand supplier dynamics, and R&D teams understand substitute threats.

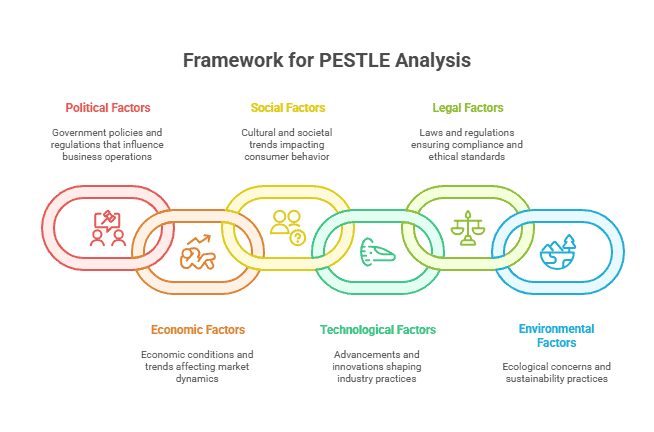

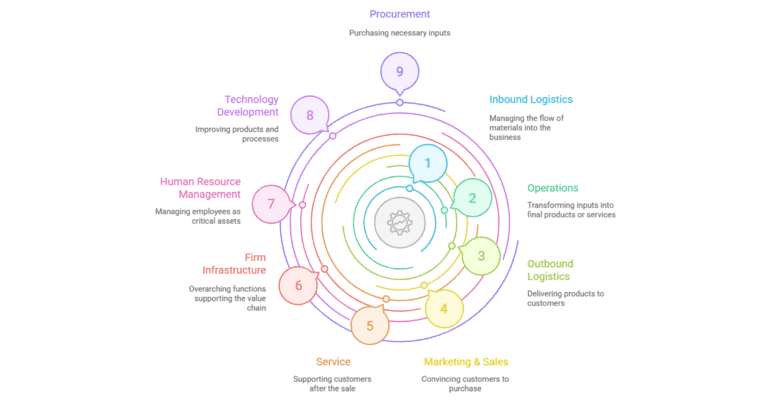

Combine with Other Frameworks: Use Five Forces analysis in conjunction with other strategic tools like SWOT analysis, Value Chain Analysis, and strategic group mapping for a more comprehensive understanding.

Consider Multiple Time Horizons: Analyze how forces might change over different time horizons. What looks attractive today might become unattractive as forces evolve.

Segment Analysis: Consider conducting separate analyses for different market segments, geographic regions, or customer groups where force dynamics might differ significantly.

Quantitative Assessment: Where possible, use quantitative data to support your force assessments. This might include concentration ratios, switching cost estimates, or price elasticity analysis.

Scenario (what-if) Planning: Consider how different scenarios might affect force dynamics. This is particularly important in uncertain or rapidly changing environments.

Regular Updates: Establish processes for regularly reviewing and updating your Five Forces analysis as industry conditions change.

Industry Examples and Applications

Porter’s Five Forces analysis varies significantly across different industries, illustrating how industry structure affects competitive dynamics and profitability.

Technology Industry: The software industry often exhibits low barriers to entry for basic products but high switching costs for enterprise solutions. Powerful buyers (large enterprises) can demand customization and competitive pricing, while the threat of substitutes is constant due to rapid innovation.

Airlines Industry: This industry demonstrates intense rivalry due to high fixed costs, low differentiation, and price-sensitive customers. High barriers to entry exist due to capital requirements and regulatory requirements.